#79. The Elementary Particles by Michel Houellebecq

This book is crazy. The entire time I was reading it, it was this heartbreaking, insanely QUIET way of writing that was incredibly real and beautifully French. But then the last chapter and epilogue came along and it was as if a giant shift occurred and everything you knew was just some tiny tiny part of a totally different thing. And not in the usual mind-blowing cliché suspense sort of way. I mean really just creatively and stylistically, this was shocking. Sudden real life sci-fi, my friends.

In the majority of the book, life can only be described as molasses. Slow, sickly with large doses, and saccharine in a stifling (and perhaps somewhat artificial) sort of way. It's true to the nature of one's every day without trying to liven it up for the sake of the reader and I like that about it. Tastes of gorgeously rendered fragments about science aren't bad either.

Such tragic characters! With every word, your heart gets a little bit heavier but you lap it up with relish. I don't think the intent is to feel sorry for these people; I at least didn't. You respect them for embodying the true, sorry face of humanity without losing integrity. Houellebecq's treatment of these desperately flawed characters is almost impeccable with their ability to voice the insecurities and unhappinesses that every adult has. Also, very clearly, he is such a smart man and it would be one heck of a thrill to be able to see inside his mind.

A writer's conversations & response to the 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die list.

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

The Yellow Wallpaper

I read The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman while I waited for my books to arrive in the mail. I was a little bit familiar with it before I discovered that it was on the 1001 list, and was rather glad that it was there. My ears had perked up any time I'd heard a reference to it, but never really had the mind to take note of it to pull it into motion.

It is the story of a woman's descent into delirium, though she may already have been on the verge to that from the beginning - I'm not quite sure. The dark, claustrophobic tone was similar to Poe's gothic style though in a slightly more relaxed voice. The cluttered, hasty style in which the writing was presented as well, was a successful way in which to present the frantic state of the speaker's mind.

I think everyone has experienced the frightful things your mind can create when staring at natural shapes. I used to sleep in a closet-sized space in my apartment in Chicago which had imperfections on the old walls that I would often identify into various likenesses. For that I think the situation that envelopes the speaker in the nursery is all the more haunting and relatable, even at a time when all of the medical injustices of the 1900s are now history.

Elementary Particles was stuffed in my teeny tiny mailbox today so I think this little guy will have the honor of being the first to be cracked open among my new book friends on my trek toward 1001.

It is the story of a woman's descent into delirium, though she may already have been on the verge to that from the beginning - I'm not quite sure. The dark, claustrophobic tone was similar to Poe's gothic style though in a slightly more relaxed voice. The cluttered, hasty style in which the writing was presented as well, was a successful way in which to present the frantic state of the speaker's mind.

I think everyone has experienced the frightful things your mind can create when staring at natural shapes. I used to sleep in a closet-sized space in my apartment in Chicago which had imperfections on the old walls that I would often identify into various likenesses. For that I think the situation that envelopes the speaker in the nursery is all the more haunting and relatable, even at a time when all of the medical injustices of the 1900s are now history.

Elementary Particles was stuffed in my teeny tiny mailbox today so I think this little guy will have the honor of being the first to be cracked open among my new book friends on my trek toward 1001.

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

The House of Mirth

I think this makes it to 100/1001! Too bad it landed on The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton because it was not really all that many thrills.

First of all, could someone please tell me what everyone's problem with Mrs. Hatch was? I don't get it. All she wanted was to marry some guy like every other female character in this book and she was somehow revolting for this. I really don't get it.

Now that that's out there, I guess I can explain why I was so let down by this. The forward talked it up by saying how "real" it was about high society in 1890s New York, and that it revealed an insider look at the world that Wharton herself grew up in and looked down upon. I was pretty excited to see some down to earth-ness and expected to see a vast difference from other books of this age (everyone seemed like they very strongly thought it was for the Austen haters out there)...but it really wasn't anything all that special. The forward also described Bart as "innocent", but I really found this to be completely false. Basically my initial perception of what I was going to be reading was all based on slanderous lies.

I guess I see how the author is pushing all her hate for this society into Lily Bart by giving her what she deserves for being a spoiled little pretty socialite, but tragedy befalling a central character is nothing ground shattering, even at that time. I would rather have read a story about Gerty than a 350+ page book about someone's self entitlement. I guess people had nothing better to amuse themselves with in the 1900s than the petty problems of rich folk, but I need a main character who is a little more aware of her surroundings rather than just concerned about where her next dress is going to come from. The afterward or whatever it was at the end of my copy said that it is a story that modern audiences cannot relate to, and I totally agree. There are books that deserve to stay in their times and remain there, and this is indeed one of them.

Anyway, I just ordered a bunch of contemporary books from Amazon and I'm pretty gosh darn excited. They are all separately coming from all over America so it's like I get a bunch of penpal packages to look forward to. Whoopee for getting yourself gifts.

First of all, could someone please tell me what everyone's problem with Mrs. Hatch was? I don't get it. All she wanted was to marry some guy like every other female character in this book and she was somehow revolting for this. I really don't get it.

Now that that's out there, I guess I can explain why I was so let down by this. The forward talked it up by saying how "real" it was about high society in 1890s New York, and that it revealed an insider look at the world that Wharton herself grew up in and looked down upon. I was pretty excited to see some down to earth-ness and expected to see a vast difference from other books of this age (everyone seemed like they very strongly thought it was for the Austen haters out there)...but it really wasn't anything all that special. The forward also described Bart as "innocent", but I really found this to be completely false. Basically my initial perception of what I was going to be reading was all based on slanderous lies.

I guess I see how the author is pushing all her hate for this society into Lily Bart by giving her what she deserves for being a spoiled little pretty socialite, but tragedy befalling a central character is nothing ground shattering, even at that time. I would rather have read a story about Gerty than a 350+ page book about someone's self entitlement. I guess people had nothing better to amuse themselves with in the 1900s than the petty problems of rich folk, but I need a main character who is a little more aware of her surroundings rather than just concerned about where her next dress is going to come from. The afterward or whatever it was at the end of my copy said that it is a story that modern audiences cannot relate to, and I totally agree. There are books that deserve to stay in their times and remain there, and this is indeed one of them.

Anyway, I just ordered a bunch of contemporary books from Amazon and I'm pretty gosh darn excited. They are all separately coming from all over America so it's like I get a bunch of penpal packages to look forward to. Whoopee for getting yourself gifts.

Thursday, September 5, 2013

"Only in my soul, sweetness"

It doesn't count, as it's not on the list, but I finished The Yiddish Policemen's Union by Michael Chabon, and felt I owed some kind of follow-up seeing as I bitched about it a couple posts back.

The story did not show substance until the last quarter of the entire novel, wherein suddenly it got incredibly sad and lonely all in the matter of a single scene. I think Chabon's flowery style does injustice to his story as well, as sifting through all of the similes and metaphors and poetic likenings were extremely tiresome and hard to focus on. I doubt that a single sentence in the entire book (not counting dialogue) was exempt from this characteristic, and it's strange to compare that to the actual plot or the personalities of its characters. I imagine Chabon to be a (well-deserved) cocky ego-maniac; something like Oprah - who's entire t.v. studio waiting area where audience members are forced to wait in line for hours before entering the studio for a taping is covered in glamour shots of herself. Though once again, having a conversation with Oprah seems much less insufferable. This image I have worked up is in no way based on reality though, so I may be eating my words in the future if I ever get confronted by an angry (or gracious) Michael Chabon.

I have recently come across so many books that redeem themselves right at the very end, and I'm not sure whether that's genius or cruel. Genius because it is the last thing the reader remembers, or cruel because you made the reader suffer through hundreds of pages of a long irrelevant ramble. The entire "mystery" that the plot revolves around also kind of seemed like a half-hearted ploy to develop character relationships, and that seemed weird to me because of how much extra work that must have taken rather than just to have made a story about a few detectives and their thoughts/pasts. A friend who's literary opinion I hold valuable recently told me that from what he remembers, he rather enjoyed the book (sans the romantic prose of course), so perhaps to each his own.

The story did not show substance until the last quarter of the entire novel, wherein suddenly it got incredibly sad and lonely all in the matter of a single scene. I think Chabon's flowery style does injustice to his story as well, as sifting through all of the similes and metaphors and poetic likenings were extremely tiresome and hard to focus on. I doubt that a single sentence in the entire book (not counting dialogue) was exempt from this characteristic, and it's strange to compare that to the actual plot or the personalities of its characters. I imagine Chabon to be a (well-deserved) cocky ego-maniac; something like Oprah - who's entire t.v. studio waiting area where audience members are forced to wait in line for hours before entering the studio for a taping is covered in glamour shots of herself. Though once again, having a conversation with Oprah seems much less insufferable. This image I have worked up is in no way based on reality though, so I may be eating my words in the future if I ever get confronted by an angry (or gracious) Michael Chabon.

I have recently come across so many books that redeem themselves right at the very end, and I'm not sure whether that's genius or cruel. Genius because it is the last thing the reader remembers, or cruel because you made the reader suffer through hundreds of pages of a long irrelevant ramble. The entire "mystery" that the plot revolves around also kind of seemed like a half-hearted ploy to develop character relationships, and that seemed weird to me because of how much extra work that must have taken rather than just to have made a story about a few detectives and their thoughts/pasts. A friend who's literary opinion I hold valuable recently told me that from what he remembers, he rather enjoyed the book (sans the romantic prose of course), so perhaps to each his own.

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

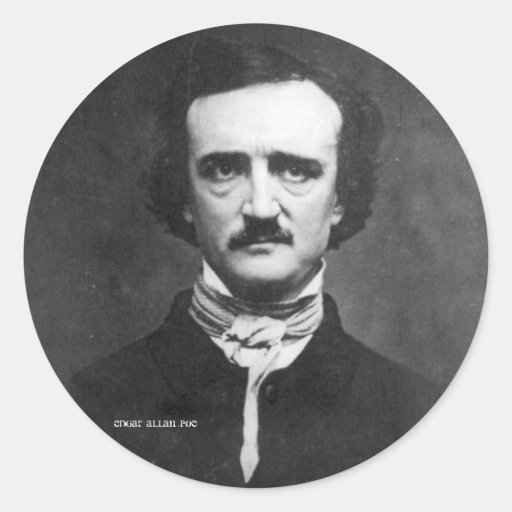

Edgar Allan Poe

The Pit and the Pendulum definitely has that iconic Poe voice. Very dark and anxious with a lot left for interpretation. It's a nice little climactic scene with even a bit of fantasy to it that touches on psychological workings. I think that the shortness of the story really works well for it and that the quick ending lends a lot of power to the buildup.

The Fall of the House of Usher is similar in these characteristics, but is haunting in a much more usual way (ghosts and mansions and the like). It reminded me of Hawthorne's The House of Seven Gables in its gothic style, though perhaps a lot of that also has to do with the fact that the titles to these stories are attributed to the houses. I'm not really sure what the point of this story was beside the fact that it was a mere form of entertainment, but I think I got more thrills from the former rather than The Fall even though it was more fitting to settings and topics that I usually prefer.

The Purloined Letter differs from these other two stories as it lacks the gloom that is so characteristic of Poe. In fact, it's got an excessive amount of "intelligent" ramble that just seems like showing off. It is, as a whole, a bit more lighthearted and comical but I don't think it engages as grippingly as the others do. There is an air of cockiness that doesn't fit the author well, and I don't think that the detective genre fits him well.

I think, in general, I'm just glad all of these stories were short.

The Fall of the House of Usher is similar in these characteristics, but is haunting in a much more usual way (ghosts and mansions and the like). It reminded me of Hawthorne's The House of Seven Gables in its gothic style, though perhaps a lot of that also has to do with the fact that the titles to these stories are attributed to the houses. I'm not really sure what the point of this story was beside the fact that it was a mere form of entertainment, but I think I got more thrills from the former rather than The Fall even though it was more fitting to settings and topics that I usually prefer.

The Purloined Letter differs from these other two stories as it lacks the gloom that is so characteristic of Poe. In fact, it's got an excessive amount of "intelligent" ramble that just seems like showing off. It is, as a whole, a bit more lighthearted and comical but I don't think it engages as grippingly as the others do. There is an air of cockiness that doesn't fit the author well, and I don't think that the detective genre fits him well.

I think, in general, I'm just glad all of these stories were short.

Monday, July 22, 2013

The Nose

Read Nikolai Gogol's The Nose yesterday on some stolen time. It read very much like The Third Policeman and I just envisioned my old Scottish co-worker friend chuckling to himself as he read this. It's kind of just a nonsensical three-part short story. Literally, a nose leaves its owner's face, turns up in a bread roll, then is somehow human-size and is wearing fancy attire as it trots away in a carriage. After all that, it miraculously appears back on its homestead face. I'm not even sure that there is any point at all. I looked it up thinking that perhaps it was a satirical commentary about society or the upper class but it doesn't really seem to be the case. There was something about masculinity and shallowness/materialism that seemed probable but in the end it might just be that Gogol was just being silly and getting paid to do it.

Outside of that, I have been trying to read Michael Chabon's The Yiddish Policemen's Union for the past few weeks but quite frankly, it's boring. BY GOD, it's so boring. I even looked it up on Wikipedia to see if I'm missing something and the only thing that I found helpful is that supposedly the Coen brothers were going to make a movie based on this book but then scrapped the script they had initially written. EVEN THE COEN BROTHERS CAN'T MAKE THIS BOOK WORTH WATCHING. If such talented gods can't even save it, it's hopeless I say! I'll probably just keep trucking at it out of sheer stubbornness until I die of boredom. Then I will rue this day.

Outside of that, I have been trying to read Michael Chabon's The Yiddish Policemen's Union for the past few weeks but quite frankly, it's boring. BY GOD, it's so boring. I even looked it up on Wikipedia to see if I'm missing something and the only thing that I found helpful is that supposedly the Coen brothers were going to make a movie based on this book but then scrapped the script they had initially written. EVEN THE COEN BROTHERS CAN'T MAKE THIS BOOK WORTH WATCHING. If such talented gods can't even save it, it's hopeless I say! I'll probably just keep trucking at it out of sheer stubbornness until I die of boredom. Then I will rue this day.

Saturday, July 6, 2013

Watchmen

Up to 95/1001 now! Wooooooo.

So...I guess I like this? I really don't know what to say. For some reason I like Rorschach the most and I feel like that makes me fucked up.

For the pace that it started off with, the ending seemed abrupt to me. I was kind of left thinking "...oh, is that the end?". For the majority of the book, it was at a really nice tempo with layered plots and character development, but once Veidt's plan was uncovered it seemed like it was kind of like "and he killed everyone and now the story is over and there is nothing else to explain or talk about, and everyone is just going to go their separate ways with little explanation". It kind of felt like a letdown.

There's a lot of violence, but it wasn't all that disturbing to me. The images were often gruesome and all but it somehow fit the grittiness so that you were never really shocked, which I kind of think is nice. There was also a lot of silhouettes of couples making out or having sex but I feel like with that part I was missing something. Maybe he just wanted NYC to be a city full of vices? Still, that seems too simple. Also, the smiley face. Was I just not paying attention, or was that never explained? Maybe I didn't have enough patience for all of these details...maybe I should go back and re-read. I'd kind of rather someone just tell me.

So anyway, I assume those movies/comics like Kick-Ass and Super and other lives-of-superheroes as real people type stories are all probably somewhat influenced by this. It's an interesting concept, and if Alan Moore was the first to think of it, that's pretty cool. I know that comic people love him and think he's a genius so I wouldn't put it past giving him that credit.

On an unrelated topic I went to Barnes and Noble to try to find some books and that store is SO FREAKING USELESS. I had about 10 titles to try to find, expecting that I wouldn't be able to find the majority of them but I could literally only find ONE. What the heck!? I guess I'm just going the Amazon route from now on.

So...I guess I like this? I really don't know what to say. For some reason I like Rorschach the most and I feel like that makes me fucked up.

For the pace that it started off with, the ending seemed abrupt to me. I was kind of left thinking "...oh, is that the end?". For the majority of the book, it was at a really nice tempo with layered plots and character development, but once Veidt's plan was uncovered it seemed like it was kind of like "and he killed everyone and now the story is over and there is nothing else to explain or talk about, and everyone is just going to go their separate ways with little explanation". It kind of felt like a letdown.

There's a lot of violence, but it wasn't all that disturbing to me. The images were often gruesome and all but it somehow fit the grittiness so that you were never really shocked, which I kind of think is nice. There was also a lot of silhouettes of couples making out or having sex but I feel like with that part I was missing something. Maybe he just wanted NYC to be a city full of vices? Still, that seems too simple. Also, the smiley face. Was I just not paying attention, or was that never explained? Maybe I didn't have enough patience for all of these details...maybe I should go back and re-read. I'd kind of rather someone just tell me.

So anyway, I assume those movies/comics like Kick-Ass and Super and other lives-of-superheroes as real people type stories are all probably somewhat influenced by this. It's an interesting concept, and if Alan Moore was the first to think of it, that's pretty cool. I know that comic people love him and think he's a genius so I wouldn't put it past giving him that credit.

On an unrelated topic I went to Barnes and Noble to try to find some books and that store is SO FREAKING USELESS. I had about 10 titles to try to find, expecting that I wouldn't be able to find the majority of them but I could literally only find ONE. What the heck!? I guess I'm just going the Amazon route from now on.

Tuesday, July 2, 2013

A Fine Balance

I suppose this story is about friendship and love through hardship, but what's coming in loud and clear is that life is hopeless so you should just give up. This is hard to grasp as an entitled asian girl in America who's family always had money and therefore had the means to keep working at getting what she wants with certainty that someday it could be attained, but as a poor person in 1975 India, I'd say that motto of "just stop trying" is pretty accurate and that basically dying was a better alternative to trying to climb the social ladder, or even to keep on living. This was supported by insane amounts of violence between religious groups and poor people, government officials and poor people, and then some weird tensions between student activists and some entity I didn't quite understand (potentially more government assholes).

If there is a movie of this book, I never want to see it because I would have nightmares forever.

Also, there is a person who is basically a pimp for beggars who's name is Beggarmaster. He keeps all of the money he collects in a suitcase that is chained to his wrist. This is not a joke and no one seems to find this strangely hilarious. He also happens to be one of the nicest characters in this book so seriously, what I'm getting at here, is India was pretty fucked up.

This was the last book I had left from Colleen's generous gift. This means I need new books. My birthday happens to be two weeks away. Wink wink.

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

Call It Sleep

Bluntly speaking, I do not like Call It Sleep by Henry Roth. It is, to be fair, very skilled in conveying a very true adolescent, but this perhaps reveals that I do not like real children (which really is no surprise). I found David Schearl to be whiney, spineless, and overly attached to his mother, which really bothers and freaks me out. I do not understand or handle well people who have strange obsessions with their parents, and it makes me very uncomfortable.

I suppose it would seem that I am being unfair by identifying a 6-9 year old boy as being annoyingly dependent, but in comparison to the other boys that surround him, Davy has been guarded from maturity because of his mother's affection. There must be a point in a child's life where he realizes he wants to be a part of others his age, I think, but it never really seems to happen with this main character. Case in point, this kid creeps me out.

Roth also does some stylistically out-of-the-box things like characterizing accents through phonetic spelling, capturing David's internal thought process through jumbled, fast moving nonsense, as well as a scene toward the end where two separate situations are woven between themselves in abrupt cuts until they collide at the climax. However avant-garde this may be (I'm blindly assuming that to be true), it was for me, very annoying and I often found myself scanning and skipping these sections because they were so hard to read, confusing, and ultimately unimportant to the bigger picture (forgettable, for lack of a better word).

The only part of the book that I found interesting was the first section, which I found to be very pretty and emotional. Not so coincidentally, this is the only section that is not written from the child's point of view. When the father tosses the child's hat overboard, it is an immensely weighted moment, and I commend Roth for such a well played choice of action for Albert Schearl to do to his newly reunited family. Props.

What I do like more than this scene, is when people share their love for a book in a very convincing manner. There is an afterword by Walter Allen in my copy that was so well-written that I started to appreciate some of his points, though not to the point that it would make me forget all of the unpleasantness I felt throughout my read.

Also, as a side-note, my copy is from 1971 and the pages look ribbed/textured when held up to the light. I am incredibly fascinated by this -- there is a sense of corrosion as well as a very handmade feel to it that I am drawn to. Also, I really like the cover image of clothes drying on a line.

I suppose it would seem that I am being unfair by identifying a 6-9 year old boy as being annoyingly dependent, but in comparison to the other boys that surround him, Davy has been guarded from maturity because of his mother's affection. There must be a point in a child's life where he realizes he wants to be a part of others his age, I think, but it never really seems to happen with this main character. Case in point, this kid creeps me out.

Roth also does some stylistically out-of-the-box things like characterizing accents through phonetic spelling, capturing David's internal thought process through jumbled, fast moving nonsense, as well as a scene toward the end where two separate situations are woven between themselves in abrupt cuts until they collide at the climax. However avant-garde this may be (I'm blindly assuming that to be true), it was for me, very annoying and I often found myself scanning and skipping these sections because they were so hard to read, confusing, and ultimately unimportant to the bigger picture (forgettable, for lack of a better word).

The only part of the book that I found interesting was the first section, which I found to be very pretty and emotional. Not so coincidentally, this is the only section that is not written from the child's point of view. When the father tosses the child's hat overboard, it is an immensely weighted moment, and I commend Roth for such a well played choice of action for Albert Schearl to do to his newly reunited family. Props.

What I do like more than this scene, is when people share their love for a book in a very convincing manner. There is an afterword by Walter Allen in my copy that was so well-written that I started to appreciate some of his points, though not to the point that it would make me forget all of the unpleasantness I felt throughout my read.

Also, as a side-note, my copy is from 1971 and the pages look ribbed/textured when held up to the light. I am incredibly fascinated by this -- there is a sense of corrosion as well as a very handmade feel to it that I am drawn to. Also, I really like the cover image of clothes drying on a line.

Thursday, May 9, 2013

The Golden Notebook

If anyone is surprised to find that I would enjoy reading a truly feminist book, it is myself. I hate "proud" feminists who rant about the power of the vagina and empowerment within the sisterhood and all that nonsense. I think if you're a strong lady, it isn't so difficult to be taken seriously and respected, and there are plenty of women who are cases of that. I myself have never been treated unfairly in the workplace or otherwise due to my sex and whether it's because I'm not "hot" enough or not, I am also not an idiot, nor am I so sensitive to feel victimized at regular human interaction.

Anyway, to move away from my bitching about feminism and onto the actual point of this blog...

I very much enjoyed The Golden Notebook, as usual, not so much based on the content of the book, but the voice behind it. I think I am in love with Ms. Doris Lessing. She mentioned a lot of things in the introductions that I simply adore. She's like a wise grandmother talking to you in complete honesty about her life experiences, and as a woman who has never had the kind of relationship or capabilities to speak in such an intimate way with her familial superiors, it was very refreshing and strange at the same time. It was kind of like talking to the me of the future, as so much of what Lessing wrote related to my own ideas. She does mention that she had received countless letters from fans of both sexes thanking her for this very notion, and I think that's very impressive in and of itself. I like this advice:

"Remember that the book which bores you when you are twenty or thirty will open doors for you when you are forty or fifty -- and vice versa. Don't read a book out of its right time for you."

The book was sometimes hard to follow because of the way it was split up. The format was an overarching story titled "Free Women" divided up into 5 parts, as well as four separate notebooks written by the protagonist on different subjects. I think I will go back and read the "Free Women" segments together as one immediately after I write this post, but otherwise I can generally say that I liked the black notebook best (about young English do-gooders in Africa), followed by the yellow one (a reflection of the Free Women parts). I like them best because they are the ones that are narrative and tell a story, whereas the red notebook was hard to understand for me because I know little about communism and the political values that were discussed there. The blue notebook's (a personal diary) purpose seemed to recount the process in which Anna started going mad, and I am slightly turned off by the topic of a character going mad at this point, since by now it is starting to be somewhat of a recycled theme.

Lessing is a very good writer. She seems to know exactly what she's doing, and takes a pretty no-bullshit approach without being annoying which I respect. It's truly the only book I've ever read that speaks in a frank way from the point of view of a woman that doesn't seem outwardly fictitious or sugary with female propaganda -- but again, I emphasize that I say this having avoided feminist writing in the past.

I should mention I moved to Ohio a little over a month ago to follow a dream. I got a job at a fashion retailer as a copywriter and although it has left me in solitude for now, I stand my ground about doing my best at being a "strong" woman and doing what it takes to reach what I want. This is not feminism, this is just being a person with conviction. It has nothing to do with sex. Being realistic about my life is something I try to maintain, and luckily I am doing better these days at having more hope so maybe it will translate in real life.

"'We've got to remember that people with our kind of experience are bound to be depressed and unhopeful.'

'Or perhaps it's precisely people with our kind of experience who are most likely to know the truth, because we know what we've been capable of ourselves?'"

Hopefully my path leads me to greater things. I suppose the core theme of this storyline is the fear of being alone and I can definitely relate to that. I am not quite happy yet, but I am trying to get there:

"I remember saying to myself, This is it, this is being happy, and at the same time I was appalled because it had come out of so much ugliness and unhappiness."

Anyway, to move away from my bitching about feminism and onto the actual point of this blog...

I very much enjoyed The Golden Notebook, as usual, not so much based on the content of the book, but the voice behind it. I think I am in love with Ms. Doris Lessing. She mentioned a lot of things in the introductions that I simply adore. She's like a wise grandmother talking to you in complete honesty about her life experiences, and as a woman who has never had the kind of relationship or capabilities to speak in such an intimate way with her familial superiors, it was very refreshing and strange at the same time. It was kind of like talking to the me of the future, as so much of what Lessing wrote related to my own ideas. She does mention that she had received countless letters from fans of both sexes thanking her for this very notion, and I think that's very impressive in and of itself. I like this advice:

"Remember that the book which bores you when you are twenty or thirty will open doors for you when you are forty or fifty -- and vice versa. Don't read a book out of its right time for you."

The book was sometimes hard to follow because of the way it was split up. The format was an overarching story titled "Free Women" divided up into 5 parts, as well as four separate notebooks written by the protagonist on different subjects. I think I will go back and read the "Free Women" segments together as one immediately after I write this post, but otherwise I can generally say that I liked the black notebook best (about young English do-gooders in Africa), followed by the yellow one (a reflection of the Free Women parts). I like them best because they are the ones that are narrative and tell a story, whereas the red notebook was hard to understand for me because I know little about communism and the political values that were discussed there. The blue notebook's (a personal diary) purpose seemed to recount the process in which Anna started going mad, and I am slightly turned off by the topic of a character going mad at this point, since by now it is starting to be somewhat of a recycled theme.

Lessing is a very good writer. She seems to know exactly what she's doing, and takes a pretty no-bullshit approach without being annoying which I respect. It's truly the only book I've ever read that speaks in a frank way from the point of view of a woman that doesn't seem outwardly fictitious or sugary with female propaganda -- but again, I emphasize that I say this having avoided feminist writing in the past.

I should mention I moved to Ohio a little over a month ago to follow a dream. I got a job at a fashion retailer as a copywriter and although it has left me in solitude for now, I stand my ground about doing my best at being a "strong" woman and doing what it takes to reach what I want. This is not feminism, this is just being a person with conviction. It has nothing to do with sex. Being realistic about my life is something I try to maintain, and luckily I am doing better these days at having more hope so maybe it will translate in real life.

"'We've got to remember that people with our kind of experience are bound to be depressed and unhopeful.'

'Or perhaps it's precisely people with our kind of experience who are most likely to know the truth, because we know what we've been capable of ourselves?'"

Hopefully my path leads me to greater things. I suppose the core theme of this storyline is the fear of being alone and I can definitely relate to that. I am not quite happy yet, but I am trying to get there:

"I remember saying to myself, This is it, this is being happy, and at the same time I was appalled because it had come out of so much ugliness and unhappiness."

Tuesday, March 5, 2013

A Passage to India

With all this unemployed time on my hands, I have taken to re-watching a ridiculous amount of Gilmore Girls (do not judge me). Lucky for me there are a crap ton of seasons and episodes within seasons, so I have been quite the bum on my couch lazing about with pretty skinny girls who eat an unrealistic amount of greasy foods while making fast, witty banter.

There is a point to me mentioning that, I swear. E.M. Forster's A Passage to India reads like something rich white people would read in the twenties...namely someone like Emily Gilmore, the old-money mother/grandmother of my beloved show. Granted, this may just be influenced by the fact that the plot and characters in this book revolve around rich British people, but I still hold this notion. F. Scott Fitzgerald would probably love it.

This one is only comme ci comme ça; it moves at an agreeable pace and the main characters are all good and likeable. Aziz is a bit of a pansy which gets annoying because his jealousies are a little bit like Harry's teenage angst phase in the J.K. Rowling series, but it's not so bad that it makes me want to stop reading or have any strong emotions.

If anything, it's a good look at friendship and the way relationships are altered by doubt. I don't think I liked anything in the entire book as much as I liked the end (the words, not the context in relation to the story or whatever political statement it may be trying to make), and I am going to go ahead and just copy them here to spoil it all for you. My apologies.

'"Why can't we be friends now?" said the other, holding him affectionately. "It's what I want. It's what you want."

But the horses didn't want it -- they swerved apart; the earth didn't want it, sending up rocks through which riders must pass single file; the temples, the tank, the jail, the palace, the birds, the carrion, the Guest House, that came into view as they issued from the gap and saw Mau beneath: they didn't want it, they said in their hundred voices, "No, not yet," and the sky said, "No, not there."'

Keep in mind those are two dudes so the weird sexual tension between two straight friends is something to look forward to if you do want to read this.

I got hired for a job today that will be taking me to Columbus, Ohio, and I feel that last bit echoing around in me a little bit like the "boum" in Mrs. Moore's head.

There is a point to me mentioning that, I swear. E.M. Forster's A Passage to India reads like something rich white people would read in the twenties...namely someone like Emily Gilmore, the old-money mother/grandmother of my beloved show. Granted, this may just be influenced by the fact that the plot and characters in this book revolve around rich British people, but I still hold this notion. F. Scott Fitzgerald would probably love it.

This one is only comme ci comme ça; it moves at an agreeable pace and the main characters are all good and likeable. Aziz is a bit of a pansy which gets annoying because his jealousies are a little bit like Harry's teenage angst phase in the J.K. Rowling series, but it's not so bad that it makes me want to stop reading or have any strong emotions.

If anything, it's a good look at friendship and the way relationships are altered by doubt. I don't think I liked anything in the entire book as much as I liked the end (the words, not the context in relation to the story or whatever political statement it may be trying to make), and I am going to go ahead and just copy them here to spoil it all for you. My apologies.

'"Why can't we be friends now?" said the other, holding him affectionately. "It's what I want. It's what you want."

But the horses didn't want it -- they swerved apart; the earth didn't want it, sending up rocks through which riders must pass single file; the temples, the tank, the jail, the palace, the birds, the carrion, the Guest House, that came into view as they issued from the gap and saw Mau beneath: they didn't want it, they said in their hundred voices, "No, not yet," and the sky said, "No, not there."'

Keep in mind those are two dudes so the weird sexual tension between two straight friends is something to look forward to if you do want to read this.

I got hired for a job today that will be taking me to Columbus, Ohio, and I feel that last bit echoing around in me a little bit like the "boum" in Mrs. Moore's head.

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

The Book of Illusions

Another Auster...I know. What am I, obsessed? Actually no. The man is a bookstore whore I tell you (both old and new, he doesn't discriminate).

The Book of Illusions is brief. I finished this baby in two days, both because it is rather short (only 9 chapters I think), but also because it is so gripping that it's hard to wrestle yourself away. The writing and plot are very contemporary, and it was refreshing to read something like that after so many classics I've dragged myself through thanks to this giant list of British-favoring titles.

It's a romance, through and through, but curiously I was never able to fall in love with the love interest Alma. It might be because I'm shallow, and she's ugly, but I was never able to openly accept her as a trustworthy character. She's very independent...and that might be it...but I also felt like she was intruding (or rather, crashing) into David's life and I was uncomfortable with that. Of course, I'm not the one in love with her, so naturally I wouldn't understand.

Auster must be a lover of films. All of the moments in the book where David is describing Mann's movies were a more than uncanny representation of many film reference titles I used while I took a ludicrous number of film classes in college. He also does a fantastic job of creating faux black-and-white films from scratch, to a seriously meticulously believable degree. It often happened that when I read those real-life critiques and analyses on film, the words on the page described the pictures and plot in such a lovely way that they were in fact much more powerful and captivating than the real thing. I got the same sense reading David's narration of the fictional films he was watching.

I did get a sense of the familiar being-overwhelmed-from-the-excess-of-misfortune residual from The Jungle, but here, I accept it as a fitting over-the-top drama genre. Besides, there is so much fancy writing/film things being done here like symbolism and foreshadowing and allusions that I'm too distracted with feelings of like.

Also, those "little people" seem like they are pure evil. That feels offensive to say.

The Book of Illusions is brief. I finished this baby in two days, both because it is rather short (only 9 chapters I think), but also because it is so gripping that it's hard to wrestle yourself away. The writing and plot are very contemporary, and it was refreshing to read something like that after so many classics I've dragged myself through thanks to this giant list of British-favoring titles.

It's a romance, through and through, but curiously I was never able to fall in love with the love interest Alma. It might be because I'm shallow, and she's ugly, but I was never able to openly accept her as a trustworthy character. She's very independent...and that might be it...but I also felt like she was intruding (or rather, crashing) into David's life and I was uncomfortable with that. Of course, I'm not the one in love with her, so naturally I wouldn't understand.

Auster must be a lover of films. All of the moments in the book where David is describing Mann's movies were a more than uncanny representation of many film reference titles I used while I took a ludicrous number of film classes in college. He also does a fantastic job of creating faux black-and-white films from scratch, to a seriously meticulously believable degree. It often happened that when I read those real-life critiques and analyses on film, the words on the page described the pictures and plot in such a lovely way that they were in fact much more powerful and captivating than the real thing. I got the same sense reading David's narration of the fictional films he was watching.

I did get a sense of the familiar being-overwhelmed-from-the-excess-of-misfortune residual from The Jungle, but here, I accept it as a fitting over-the-top drama genre. Besides, there is so much fancy writing/film things being done here like symbolism and foreshadowing and allusions that I'm too distracted with feelings of like.

Also, those "little people" seem like they are pure evil. That feels offensive to say.

Tuesday, February 26, 2013

The Jungle

For all the dislike I have of Chicago, I must say that at least I wasn't here in the early 1900s. Compared to that, I'm living the life of a queen. Jurgis Rudkus' life is, plainly stated, shit. I would have gone mad and killed myself long ago in his situation, which I must admit, I wish he had done so that the book would have stopped much sooner. But while we're on the topic of dislike -- I'm just going to come out and say it -- I have no desire to read any more Sinclair ever again.

I don't even know how to organize my thoughts, so I will keep it brief. Here is a list of rants in order of my beef (hardy har har) with them:

1. What is the point of the last two chapters!? I am aware, thanks to the notes at the end of the book, that the audience for this story was Socialists. But for the sake of modern times, all of the goddamn speeches should have been cut. Jesus, the only thing I could think the whole time was that I could not wait for it to end. It stopped even being about Jurgis at all, since he didn't even speak for almost the entire part of the last 50 pages or more.

2. When the book was revolving around Jurgis, it was ludicrous. Okay, I understand times were tough and people keeled over and died all the time and were dirty and poor etc etc but each chapter LITERALLY ended with a new dramatic calamity that befell the main character. Out of a job? One up that, all your money is taken. Oh, your house got foreclosed? Welp, now your wife is dead. At least you still have that ray of sunshine in your life that's your son. Oh wait, now he's randomly dead too even though he was super healthy two pages ago.

3. There is absolutely no humanizing any of the women. Sure, Jurgis loved Ona but she was a flat character who was an idiot. Elzbieta and Marija seemed so strong and had so much potential but instead, they ended up just being little puppet vessels for the sake of Jurgis who became incredibly dull as soon as he left his family. And then once Jurgis does come crawling back after betraying them, they take him in without any questions because they are so wonderful and kind. What the heck. Feminism!

4. Prior to starting this book I kept hearing how great it was. All of these comments came from men, naturally, and I can see why they may say that because it's all rough around the edges and masculine and all about hard work and all that. Honestly, I don't need beautiful images and emotion and puppies and marshmallows if the content is good, and I truly sincerely would appreciate a story about someone working through hardship and trying their best. But I cannot handle this book. It is just too much whining and self loathing, and nothing is even resolved in the end.

At least this book taught me why there are so many Lithuanians in Chicago (yes, I have lived here for over 5 years and do not know any history about the city). It also taught me that Lakeshore Drive was lined with mansions, which seems obvious, but it's nice to see that all of those old buildings over there that I used to drive by on the bus daily actually are historical. Guess that much really hasn't changed. Well, you know, class and society-wise...not people-melting-in-lard-vats-and-getting-eaten-alive-by-rats-at-work-wise.

I don't even know how to organize my thoughts, so I will keep it brief. Here is a list of rants in order of my beef (hardy har har) with them:

1. What is the point of the last two chapters!? I am aware, thanks to the notes at the end of the book, that the audience for this story was Socialists. But for the sake of modern times, all of the goddamn speeches should have been cut. Jesus, the only thing I could think the whole time was that I could not wait for it to end. It stopped even being about Jurgis at all, since he didn't even speak for almost the entire part of the last 50 pages or more.

2. When the book was revolving around Jurgis, it was ludicrous. Okay, I understand times were tough and people keeled over and died all the time and were dirty and poor etc etc but each chapter LITERALLY ended with a new dramatic calamity that befell the main character. Out of a job? One up that, all your money is taken. Oh, your house got foreclosed? Welp, now your wife is dead. At least you still have that ray of sunshine in your life that's your son. Oh wait, now he's randomly dead too even though he was super healthy two pages ago.

3. There is absolutely no humanizing any of the women. Sure, Jurgis loved Ona but she was a flat character who was an idiot. Elzbieta and Marija seemed so strong and had so much potential but instead, they ended up just being little puppet vessels for the sake of Jurgis who became incredibly dull as soon as he left his family. And then once Jurgis does come crawling back after betraying them, they take him in without any questions because they are so wonderful and kind. What the heck. Feminism!

4. Prior to starting this book I kept hearing how great it was. All of these comments came from men, naturally, and I can see why they may say that because it's all rough around the edges and masculine and all about hard work and all that. Honestly, I don't need beautiful images and emotion and puppies and marshmallows if the content is good, and I truly sincerely would appreciate a story about someone working through hardship and trying their best. But I cannot handle this book. It is just too much whining and self loathing, and nothing is even resolved in the end.

At least this book taught me why there are so many Lithuanians in Chicago (yes, I have lived here for over 5 years and do not know any history about the city). It also taught me that Lakeshore Drive was lined with mansions, which seems obvious, but it's nice to see that all of those old buildings over there that I used to drive by on the bus daily actually are historical. Guess that much really hasn't changed. Well, you know, class and society-wise...not people-melting-in-lard-vats-and-getting-eaten-alive-by-rats-at-work-wise.

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

Waterland

#265. Waterland by Graham Swift (no, not the Kevin Costner movie that you're thinking of).

I like this book because it doesn't end happily in the mainstream fashion that is so frequent these days. Or else, I guess that's the case in movies...but I suppose books tend to lend themselves to more sobering characters, which have depth and grey emotions.

My point is -- if that is actually the case and I'm not just generalizing and being an idiot -- this book does a good job of being a book. There is a fine balance of heaviness, humor, and brightness as there truly is when one looks back on their life, and I think Swift's ability to capture true human thoughts and emotions like childish love, doubt, regret, and curiosity is really apparent here.

The novel is laid out in a nice way, through the stories of a history teacher narrating his "history" to his students. What a lovely concept, when you consider it. I wish I could have that kind of experience - it's a rare thing to really hear about and understand someone's past (at least for me), especially when you weren't a part of it, and when it happens, it's something quite magical.

Tom Crick's story is sincere, and really truthful in the sense that life is full of impulses, heartache, confusion, and the sense that we are all trapped in the past. I have a love affair with the topic of memories, so of course, this hits me right where I am vulnerable, but aside from that, I think there is really something that makes you think here.

One thing that I thought was a little bit weak, was Ernest Atkinson's reasoning for putting those 12 bottles of beer into the chest for Dick (also, the significance of the name Richard). Ernest referred to them "for emergencies" but what the hell kind of emergency is he really envisioning potent beer to be useful for? Come on, be a little bit more useful to your son that you forced your daughter to have. Perhaps it was just a random out for Swift to exemplify Ernest's insanity as well as being able to use it as a way for the ultimate destruction of Dick in order to come full circle, but there must have been much better ways to tie things up.

There is no happy ending to real life because it just keeps going, and I think that's something that Waterland makes you consider. I guess all anyone can do is to live until you die and to do your best. I'll be on the road again on the way to some more interviews next week. Wish me luck!

I like this book because it doesn't end happily in the mainstream fashion that is so frequent these days. Or else, I guess that's the case in movies...but I suppose books tend to lend themselves to more sobering characters, which have depth and grey emotions.

My point is -- if that is actually the case and I'm not just generalizing and being an idiot -- this book does a good job of being a book. There is a fine balance of heaviness, humor, and brightness as there truly is when one looks back on their life, and I think Swift's ability to capture true human thoughts and emotions like childish love, doubt, regret, and curiosity is really apparent here.

The novel is laid out in a nice way, through the stories of a history teacher narrating his "history" to his students. What a lovely concept, when you consider it. I wish I could have that kind of experience - it's a rare thing to really hear about and understand someone's past (at least for me), especially when you weren't a part of it, and when it happens, it's something quite magical.

Tom Crick's story is sincere, and really truthful in the sense that life is full of impulses, heartache, confusion, and the sense that we are all trapped in the past. I have a love affair with the topic of memories, so of course, this hits me right where I am vulnerable, but aside from that, I think there is really something that makes you think here.

One thing that I thought was a little bit weak, was Ernest Atkinson's reasoning for putting those 12 bottles of beer into the chest for Dick (also, the significance of the name Richard). Ernest referred to them "for emergencies" but what the hell kind of emergency is he really envisioning potent beer to be useful for? Come on, be a little bit more useful to your son that you forced your daughter to have. Perhaps it was just a random out for Swift to exemplify Ernest's insanity as well as being able to use it as a way for the ultimate destruction of Dick in order to come full circle, but there must have been much better ways to tie things up.

There is no happy ending to real life because it just keeps going, and I think that's something that Waterland makes you consider. I guess all anyone can do is to live until you die and to do your best. I'll be on the road again on the way to some more interviews next week. Wish me luck!

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

The Plot Against America

Roth does this thing in The Plot Against America where instead of building up to a major dramatic climax where everything hits the fan at once and turns into holy-shit-chaos like in American Pastoral, he rather casually introduces startling little facts and effects upfront and explains them later which results in tiny little chaos slaps in the face. Something along the lines of "I snuck out of my house to become an orphan and everything really turned out fine and I don't even remember getting kicked by that horse and why I'm now hooked up to a tube"...which then goes on to explain how he came upon a horse and why it decided to kick him in the head. In better words, of course. The overall story though, is a what-if-Lindy-had-been-president-instead-of-FDR fictionalized history told through the accounts of Philip Roth as a young boy in New Jersey. This means that America grows to be an anti-semitic nation led by a supposed supporter of Hitler. I've never really read/seen anything about America's involvement with WWII prior to Pearl Harbor, so this was an interesting place to start.

I'm really impressed by the way Philip Roth can complexly think things through and write in such a detailed manner pertaining to various characters, and how things affect one another. I'm a simpleton so I'm unable to conceptualize one person's actions and motives and how they will build into a bunch of other events and thus my stories are flatter than this rich faux history that Roth has created. It's believable, exciting, and personal, and you get the sense that you're actually learning something about history even though it's not what really happened (although, you can get a quick taste of the learning bit of real events from the postscript). As I've mentioned before, I've often found that Jewish writers are exceptional at capturing emotion beautifully (whether it's Nazi-related or not), and by using his own family as the centerpiece of the story, Roth has written a sort of upside-down fairy tale of his own life that is relatable.

All this WWII reading led me to other movies and online reading and now I'm kind of paranoid, though I'm not sure of what. Also, I didn't know Henry Ford was such an anti-semite. What an asshole.

Going to Boston next weeeeeeek! Dear god, let someone freaking hire me soon because this job hunt thing is really getting expensive.

I'm really impressed by the way Philip Roth can complexly think things through and write in such a detailed manner pertaining to various characters, and how things affect one another. I'm a simpleton so I'm unable to conceptualize one person's actions and motives and how they will build into a bunch of other events and thus my stories are flatter than this rich faux history that Roth has created. It's believable, exciting, and personal, and you get the sense that you're actually learning something about history even though it's not what really happened (although, you can get a quick taste of the learning bit of real events from the postscript). As I've mentioned before, I've often found that Jewish writers are exceptional at capturing emotion beautifully (whether it's Nazi-related or not), and by using his own family as the centerpiece of the story, Roth has written a sort of upside-down fairy tale of his own life that is relatable.

All this WWII reading led me to other movies and online reading and now I'm kind of paranoid, though I'm not sure of what. Also, I didn't know Henry Ford was such an anti-semite. What an asshole.

Going to Boston next weeeeeeek! Dear god, let someone freaking hire me soon because this job hunt thing is really getting expensive.

Sunday, January 6, 2013

I'm glad Kafka let this one go

I have so far found for myself that Franz Kafla's writing doesn't suit me. He is rather melancholy and depressing, which you would think would be right up my alley, but he does it in such a queer way that is impersonal and difficult to relate to.

The Trial is an unfinished novel, so that probably accounts for all of the loose ends in this story (such as the female neighbor that K. stalks for a chapter or so and then immediately forgets). The topic of this novel is an accused man who is "arrested" for no apparent cause. Naturally, you would assume that with that sort of "problem", the point of the plot would be to reveal what the accused had done. On the contrary, no one (not even the reader) cares at all why this might be, and on top of that, the entirety of the 10 chapters are so nonsensical with no apparent motive to bring purpose to anything that occurs on a single one of the pages that make them up.

K. does seem to be weirdly and abruptly sexual with random women who he just happens to meet as strangers though, so maybe he was arrested for being a man slut. Whatever the case, I'm not much interested in investigating any further than not at all.

For my next book, I'm going back to an author I could relate to a little better.

The Trial is an unfinished novel, so that probably accounts for all of the loose ends in this story (such as the female neighbor that K. stalks for a chapter or so and then immediately forgets). The topic of this novel is an accused man who is "arrested" for no apparent cause. Naturally, you would assume that with that sort of "problem", the point of the plot would be to reveal what the accused had done. On the contrary, no one (not even the reader) cares at all why this might be, and on top of that, the entirety of the 10 chapters are so nonsensical with no apparent motive to bring purpose to anything that occurs on a single one of the pages that make them up.

K. does seem to be weirdly and abruptly sexual with random women who he just happens to meet as strangers though, so maybe he was arrested for being a man slut. Whatever the case, I'm not much interested in investigating any further than not at all.

For my next book, I'm going back to an author I could relate to a little better.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)